When considering the lifestyle aspect of space travel, it’s worth noting that our ancient bond with animals has extended into space.

Human connection with animals began over 15,000 years ago with hunting partnerships with wolves, which evolved into domesticated dogs. Sheep, goats, pigs, cows, and cats were domesticated next, becoming fixtures in early settlements. Mice crashed the gathering by seeking out food stores.

Perhaps inevitably, animals not only accompanied humans into space but preceded us, playing a vital, sometimes sacrificial role. By flying first, they helped identify what conditions were safe and what weren’t for human space travel.

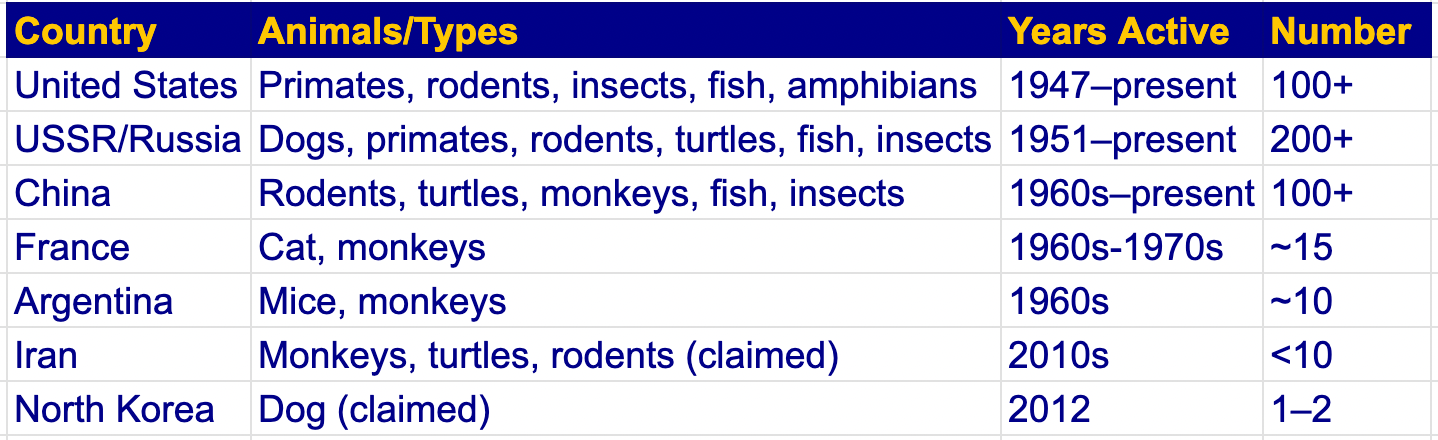

Fruit flies went first, followed by dogs, monkeys, turtles, and one cat, each facing extreme risk and frequent fatalities. Each mission advanced scientific understanding, paving the way for human missions.

Today, most animal space research involves small species aboard the ISS and Chinese space station. Mice, fruit flies, tardigrades, fish, and insects are studied to understand how microgravity impacts biology, aging, radiation, and development. This research is vital to improve long-duration missions.

Animal Pioneers and Scientific Contributions

The first creatures sent to space were fruit flies, launched by the U.S. in 1947 aboard a V-2 rocket to study radiation. In 1948, Albert I, a rhesus monkey, became the first vertebrate in space, though he did not survive. These early missions laid the foundation for more complex biological experiments.

The Soviet Union, and later Russia, remains the only nation known to have sent dogs into space. Between the late 1940s and early 1990s, at least 57 dogs flew suborbital and orbital missions. These missions relied on Moscow strays, selected for their toughness and trained for high-stress environments, to test life support, microgravity tolerance, and recovery systems.

The most famous of these canine cosmonauts was Laika, launched aboard Sputnik 2 in 1957. Although she died of overheating hours after launch, her mission proved that mammals could survive launch and orbital conditions and led to advances in life-support design. In 1960, Belka and Strelka completed the first full-day orbital mission and returned safely with a rabbit, mice, and plants. The flight demonstrated full mission survivability and served as a precursor to Yuri Gagarin’s flight, the first crewed orbital mission in history.

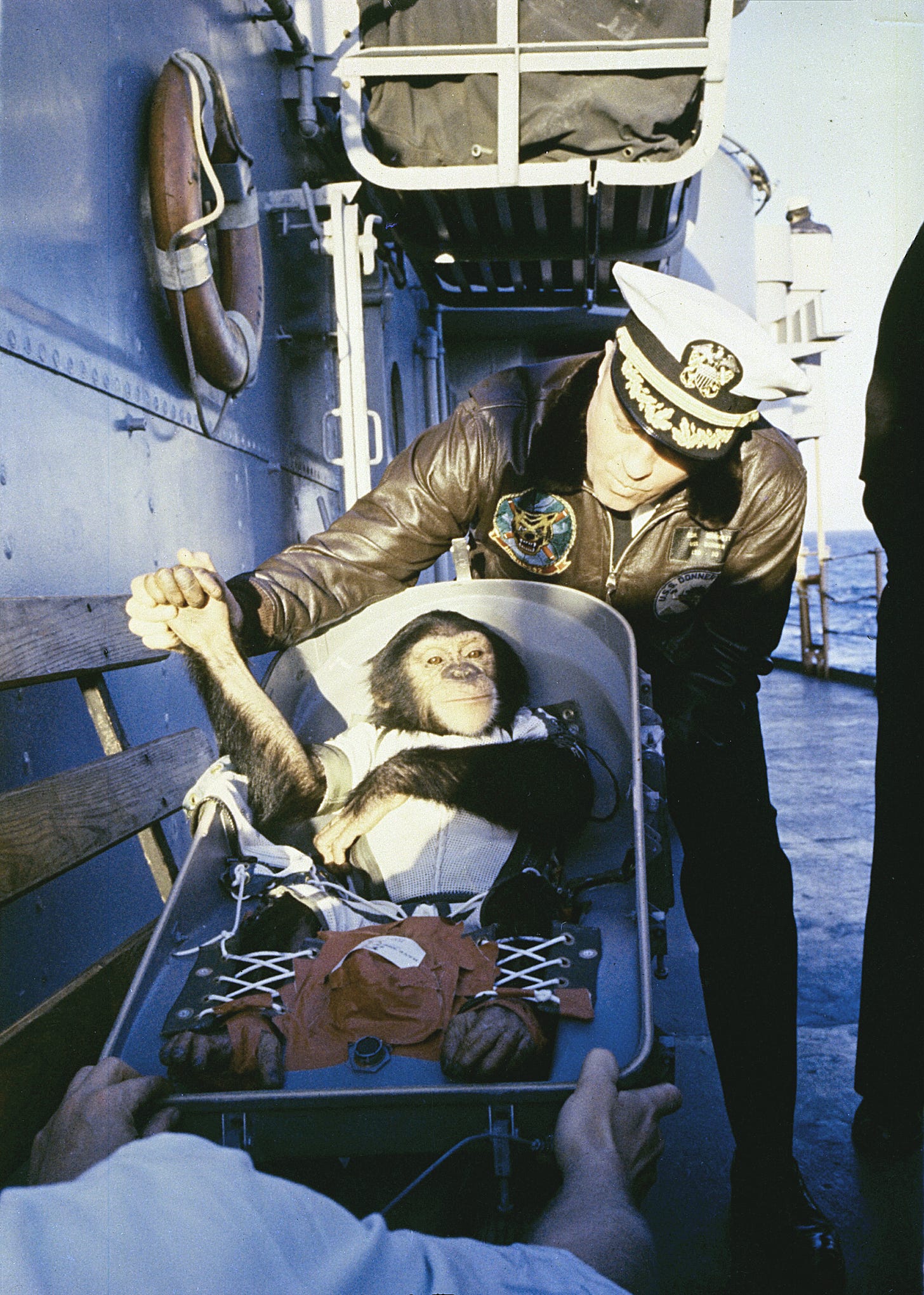

In contrast, the United States employed primates for their physiological and neurological similarity to humans. Between 1948 and 1996, at least 32 monkeys including rhesus, squirrel monkeys, and chimpanzees participated in space missions. Many died during or after flight, but they provided valuable insights into behavior, cognition, and survival in space.

Ham the chimpanzee, launched in 1961 aboard Mercury-Redstone 2, and Enos, later that year on Mercury-Atlas 5, were key to proving humans could follow. Ham performed tasks in microgravity, confirming trained beings could function in space. Enos became the first U.S. animal to orbit Earth, completing two orbits and operating levers despite malfunctions. His mission validated life-support systems and cleared the way for John Glenn’s 1962 flight.

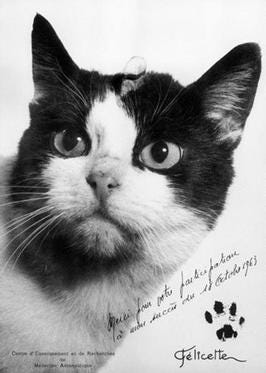

Other nations contributed to early research. In 1963, France sent a cat named Félicette on a suborbital flight to study neural activity. She survived and remains the only feline astronaut to date.

Animal travelers advanced science in critical ways. Frogs and fish showed how the inner ear adapts to microgravity and helped explain motion sickness. Rodents revealed rapid bone and muscle loss, informing astronaut training. Mice exposed to cosmic radiation highlighted DNA damage risks, while cardiovascular shifts, hormone regulation, and reproduction were all first studied in animals.

These animals laid the scientific groundwork for human space exploration, providing essential data on how life endures beyond Earth. Without them, the first human spaceflights by Gagarin and Glenn might not have launched when they did.

Soviet Legacy and Successor Claims

After the U.S. ended its animal spaceflights in the 1970s, the Soviet Union continued into the 1990s, focusing on primates aboard its Bion satellites. Early missions featured dogs, but later flights used rhesus macaques to study long-term effects of microgravity with most animals safely recovered.

Iran revived interest in the 2010s, launching turtles, mice, and monkeys on suborbital rockets. The most publicized was in 2013, when Iranian media claimed a monkey named Fargam reached space and returned. Inconsistencies in photos raised skepticism, and no international body confirmed the mission. Though framed as steps toward human flight, the credibility remains disputed.

North Korea has claimed to launch animals into space, including a dog in 2012, but these reports remain unverified and are widely viewed as propaganda.

Modern Missions and Ongoing Research

Animal research remains central to space science. So far in 2025, the ISS has hosted mice, fruit flies, tardigrades, and small fish to study bone loss, immune function, aging, and DNA repair. These organisms serve as human analogs, helping researchers understand muscle atrophy, circadian disruption, and radiation effects. Most are housed in controlled habitats and returned safely to Earth, supporting preparation for longer missions to the Moon or Mars.

China’s Tiangong Space Station is also expanding biological research. As of mid-2025, it hosts zebrafish for vertebrate studies and fruit flies for genetics and circadian rhythm research. Planarian flatworms will soon follow to explore regeneration.

The Future of Animals in Space

Looking ahead, animals may play new roles as spacefarers. As Artemis missions push toward permanent lunar and Martian outposts, questions of agriculture and companionship arise. Could chickens lay eggs in lunar greenhouses? Would goats or rabbits adapt to microgravity farms?

The number of people inhabiting space is increasing, typically averaging around 10 aboard the ISS and Tiangong combined, with more during crew changeovers. A record 19 was reached in 2023, with 13 on stations and six briefly in space on a Blue Origin flight. By 2035, five new stations could push capacity to 70 people.

With the growing station population and rise of space tourism, it seems only a matter of time before someone takes a pet. Would a passenger pay $2.5 million for their pet to occupy a seat as the first private animal on a suborbital flight? Time will tell.